This is an abridged version of the ''Finding Pride" story, originally published on the Harvard Business School's Alumni website.

In the late 1970s, a dozen or so gay men found one another at HBS and decided to band together, calling themselves the Alternative Executive Lifestyles group.

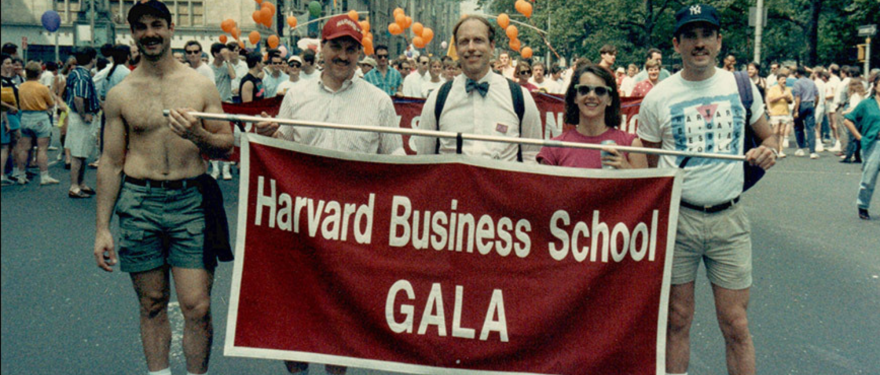

They posted notices around campus, discreetly inviting fellow gay and lesbian students to connect via an untraceable off-campus phone number. Those founding members launched what would become a decades-long tradition—a community within the community. The group’s name, originally borrowed from a similar group at Stanford, would evolve over time; its membership and public presence did, too. Today the PRIDE group is an association of 190 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ+) students and partners. It serves as a social and professional network, as well as a place to promote community and encourage advocacy for LGBTQ+ individuals at the School and in the world of business. Here, in honor of Pride Month, we hear about the role the student club played in the lives of some of those who belonged over the years.

1970s

“I was scared to death that someone would figure out where it came from, but I typed up a letter to my section saying that there are gay people around you, you just don’t know it.”

I was in the closet when I arrived at HBS. We all were. You had to be.

I was ultimately introduced to Ernie Phinney (MBA 1978), who was one of the founders of the Alternative Executive Lifestyles group. He also told me to try out for the B-School Show, because half the cast and crew were gay and lesbian. That year we had about 15 people in the group, with 7 or 8 per class. I went to an alumni event recently with about 20 guys who were about five years out of school, and they laughed hysterically at the name. They were incredulous that we couldn’t just say what the club was, but the reality was that we were afraid of being shunned.

There was an incident in my first year where one guy was making jokes in class. I was scared to death that someone would figure out where it came from, but I typed up a letter to my section saying that there are gay people around you, you just don’t know it. David Kusin (MBA 1979) was a reporter for the Harbus, and he published my letter. There was an uproar, and one classmate started spreading the word that David wrote the letter and was part of the radical gay liberation movement. He had nothing to do with it, except to coordinate with me to publish it. He took a lot of heat for me back then. Thanks, David!

In my second year, when I was looking for a job as a commercial and investment banker, I would look at their policies for nondiscrimination. Most banks had nothing, but Bank of America, Chase, and Citibank all did, so that’s where I applied. I decided on San Francisco-based Bank of America because they had a longstanding policy; the reality was, if you had a boss who was homophobic or uncomfortable, it didn’t matter. One of my goals in going to business school was to start my own business, so that my sexuality wouldn’t be an issue. Once I started working on my own, particularly with a business partner who was also gay, we didn’t worry too much about anything. Now I’ve been with my husband, Bob Holley, for 43 years. Last October, I was in the hospital for a few weeks, and Bob would come every afternoon to spend the day with me. I’d introduce him around as my husband; no one batted an eye. I never imagined we’d see this happen.

—Paul Raeder (MBA 1979)

1980s

“Any leadership skills I may possess came from this club that dared not speak its name and that constituted the center of my world.”

It wasn’t easy to be gay in the 1970s—not that it ever was.

Anita Bryant was spewing vitriol, Harvey Milk was murdered in November 1978, and six months later I was ostracized and driven out of my company when I was seen on the evening news speaking at a gay rights rally.

I arrived at HBS in 1980. There seemed to be no one like me—a lefty, feminist English major, and most of all, gay—in this conservative, straight white male world, with a not insignificant contingent of what was referred to as the “3Ms”: military, Mormons, and McKinsey. I lived in fear that my true identity would be discovered.

The Gay Students Association (GSA) got me through. We were deeply underground because we had to be, but every month we had a party, often with dancing, and it was joyous. In the spring term of my first year, the alumni group started up an annual potluck in New York City, and 10 or 12 of us would drive down to meet 60 to 70 wonderful, accomplished gay and lesbian alums. I was co-president of the GSA my second year, and after graduating I organized 15 of the NYC annual potlucks and served as both president and co-president of the alumni group. HBS, with its many clubs and opportunities, is all about leadership. Any leadership skills I may possess came from this club that dared not speak its name and that constituted the center of my world.

We had a lot of losses in the club from HIV/AIDS, and I’d like to say their names: My friends Jeff Eisberg (MBA 1979), one of our founding members; Bart Rubenstein (MBA 1979); Raul Companioni (MBA 1980); Bob Anderson (MBA 1982); Jim Savage (MBA 1977); Paul Williamson (MBA 1983); and Phil Kanner, life partner of my dear friend Steve Mendelsohn (MBA 1984).

We also lost Harley Uhl (MBA 1975); Philip Burkett (MBA 1976); Frank La Penta (MBA 1977); Dan Brandeberry (MBA 1978); Joe Hilliard (MBA 1978); Mark Landsberger (MBA 1978); Rob Rosecrans (MBA 1979); Peter Hollinger, M.D., partner of Jon Zimman (MBA 1980); Michael Russell (MBA 1980); James Janke (MBA 1980); Ric Angulo (MBA 1983); John Kemp (MBA 1981); Fred Mann (MBA 1983); Ravenell “Ricky” Keller (MBA 1989); and Richard Zayas (MBA 1996). These are only the ones about whom we know. I found out about Ric Angulo when I went to Central Park to see the AIDS quilt in 1988 and saw his name. He had only just died. Someone had written, “Ric, I wish we’d known.”

—Virginia Smith (MBA 1982)

1990s

“I assured them I was a lesbian, and I wasn’t there to out them. That’s what the climate was like at the time.”

By second semester of my first year, I was a writer for the Harbus; I wasn’t out, and I didn’t really have a network of friends.

One Friday night, when I wasn’t up for drinking at the straight bars, I got the courage to call the number for the Gay and Lesbian Students Association (GLSA) and asked if they were meeting. “We’d love to have you,” a voice on the phone said. As I walked across the bridge in freezing snow, I almost turned back. But I trudged on and rang the doorbell, and the man who matched the voice on the phone welcomed me. When I stepped inside, someone shouted, “Annette!” I looked around and saw one of my professors, Willis Emmons (MBA 1985). Someone else gasped, and a few people looked extremely nervous. I realized they were terrified that I was one of the undercover writers of the Gang of Nine, who wrote the anonymous gossip column for the Harbus. I assured them I was a lesbian, and I wasn’t there to out them. That’s what the climate was like at the time.

The connection to fellow alumni of the GLSA has proven to be lifelong. There’s a deeper layer of connection with people who’ve gone through similar experiences, and to have that bond mashed together with the aspiration of being business leaders—that’s been the foundational strength in my career. I came out in my first job interview in 1990. When the owner of the company asked if I had any other questions, I made clear that insurance coverage for my domestic partner was a condition of my employment, which wasn’t really done then. Had I not had the fortitude of friends, and the HBS GLSA network, I don’t think I’d have been as strong of a person entering the workforce as I was.

—Annette Friskopp (MBA 1990), coauthor of Straight Jobs, Gay Lives: Gay and Lesbian Professionals, the Harvard Business School, and the American Workplace (1995) with Sharon Silverstein (MBA 1990)

2000s

When we arrived on campus, they drilled into us that one of the values of HBS is the network and the connections you make there.

I think the words the Dean used were to the effect of, “You have to invest in each other.” I’m from a very conservative environment in Mexico; I wasn’t out to my family yet, and there was a lot of trepidation as to how I would navigate that. After a couple of weeks, I decided to come out to my section and was disappointed that some people who’d been friendly with me cooled after that. Others were supportive. Luckily, I ended up sitting next to someone in my first year who became a close friend. Together with another friend, we led the Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Student Association (GLBSA) during our second year, which was a tight-knit group of about 15 members. We objected to President Larry Summers’s decision to allow military recruiters on campus, since they banned gays or lacked non-discrimination protections for gays.

In my 25 years in corporate America, I’ve seen a positive evolution, but more work remains. I’ve been with my husband for over 18 years, and when people see my ring, many ask about my wife. I simply reply that my husband is from Australia. Most people take it in stride. Most large companies now have policies to provide protection for LGBTQI+ employees. But getting ahead often requires building personal relationships, and that’s where I feel there may still be some hidden homophobia. I hope that becomes a thing of the past as new business leaders continue to drive positive change.

—Javier Bordes-Posadas (MBA 2004)

I came out between college and grad school, so I wasn’t part of a PRIDE equivalent in undergrad, but I was intrigued with the idea of being involved at HBS.

When I got to campus, I organized a pizza night for the WTGNC [women, trans, and gender nonconforming] contingent of the RCs. About 15 people showed up—and that’s where I met all my closest friends. The WTGNC contingent came from a desire to make sure there’s a community within PRIDE for folks who experience marginalization as a result of their gender identity. This year, about 75 of the 195 members of PRIDE are WTGNC.

PRIDE is really about creating community for people who are marginalized in society and in the business world. It’s a space where people can gather and share and be parts of themselves that they cover or don’t feel comfortable sharing at HBS. For me it shows how important it is to have affinity groups and spaces to bring people together around identity and shared experience. It’s really been home for me at HBS.

—Nicolle Richards (MBA 2023)