We recently asked 600 CEOs: What is keeping you awake at night during this global pandemic? A major and multifaceted concern that emerged is how to keep employees motivated when their world is crashing around them. The circumstances of work have become more difficult. Their responses included:

- “Keeping morale and motivation up amongst employees while they are dealing with the stress of COVID-19 as well as parenting/schooling children while working from home. How can we be supportive while maximizing productivity? How do we help employees with work/life balance?”

- “How to keep people engaged and connected and OPTIMISTIC in appropriate measure while so many have so many competing personal and business and health and family issues right now.”

Meanwhile, cost-cutting, uncertainty, and the necessities of social distancing attenuate or alter the traditional organizational levers. Several CEOs observed:

- “Keeping spirits high in a sales environment. At the moment our sales force has to work twice as hard for a quarter of the results. We have reduced the expectation of results but they still feel like they are losing every day. I believe this will be a marathon, not a sprint, and I will need help for the next many months to keep theirs and others’ spirits high so we can keep them for when we recover.”

- “How to motivate a team that has been furloughed? With our operations totally shut down by the government, we had to furlough 90% of our team. They still receive benefits but no wages. We plan on bringing them all back as soon as we are allowed to reopen, but for now they have no income from the company. Many in our industry laid off their employees, we did not.”

- “How to keep executives motivated who were asked to take a 50% salary reduction. Because we are now closed and have no revenue, we asked senior staff to take a 50% pay reduction until we reopen. Our CEO took a 100% pay reduction.”

On the positive side of the spectrum, CEOs report that their teams are eager to be motivated, to find meaning at work during this crisis.

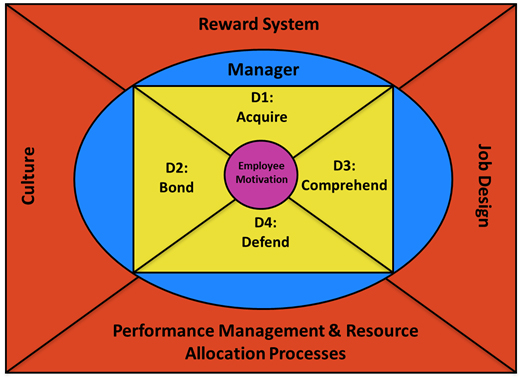

Research by Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria and colleagues suggests that people are guided by four basic emotional needs, or drives, that are the product of our common evolutionary heritage. These four drives—the “ABCD” of human motivation—are:

- Acquire. Obtain scarce goods, including intangibles such as social status.

- Bond. Form connections with individuals and groups.

- Comprehend. Satisfy our curiosity and master the world around us.

- Defend. Protect against external threats and promote justice.

The extent to which a job satisfies these four drives accounts for a large portion of how much an individual is motivated in their work. While improving the fulfillment of any one drive enhances employee motivation somewhat, the key to a major employee-motivation advantage relative to other companies comes from improving all four drives in concert.

To some extent this is because of the balance required between two pairs of drives.

The drives to acquire and to bond are in tension with each other because the first is competitive and the second cooperative. A major part of management is to keep these two drives in healthy balance, for example by giving rewards for both individual and team performance. Without direct oversight, “Relationships can all too readily slide into cutthroat competition or totally collusive bonding. Either extreme will harm the firm's performance.”

Less obviously, the drives to comprehend and to defend are also on opposite ends of the spectrum. Learning requires openness, the willingness to fail and lose, to move into unknown territory. This is the very opposite of the drive to defend territory and status. Both of these drives, likewise, can go to extremes. On the one hand, an individual or organization could become so intoxicated with experimentation and learning for its own sake that they have no strategy. On the other hand, one becomes so determined to hold on to territory and advantage that they resist change and even information.

Organizations can balance these drives by allocating rewards and resources for both traditional performance and for learning activities.

What has changed and what hasn’t?

The four drives themselves, fundamental to human psychology, have not changed. The COVID-19 pandemic has not altered these dynamics as much as it has intensified or complicated them:

- Cost-cutting and remote work mean that both the acquisition and bonding drives are harder to meet via traditional means such as raises and team outings.

- Uncertainty around the pandemic itself, and its effect on industries and governments, have increased people’s comprehension and defensive drives.

- The implicit, almost unconscious ways we get information and reassure each other are lost when people go remote. Colleagues are not going to overhear useful conversations while getting coffee. Because of this, functions of leadership that may have been automatic must now be done explicitly and with intent. The implication for leaders: overcommunicate, and over-reinforce boundaries and expectations.

- While organizational policies are the infrastructure of meeting employees’ four drives, managers implement those policies and can do so in ways that increase or decrease engagement. Subcultures within organizations can differ as much as organizational cultures themselves. Most people have encountered a team that performs well above—or below—the organizational norm. While this has always been the case, widespread moves to remote work mean that individual managers are now, for many employees, the only face of the company that they interact with. This greatly increases the importance of managers.

A big question remains. What can organizations and team leaders do to increase fulfillment of each of the four drives? The graphic below displays the four-drive ecosystem.

Acquire/Achieve

On the organizational level this drive is usually met through the compensation and rewards system. Best practices include:

Pay as well as competitors. There can be exceptions; the need to acquire applies to intangibles as well. Organizations with good reputations may be able to attract talent at a discount; the reverse may be true for stigmatized organizations. Likewise, investments in employees’ long-term prospects via continuing education/development or ownership options may allow for a discount in pay.

Sharply differentiate good performance from average and poor performance. This should be based on metrics that are clearly tied to the company’s mission. Note that we say performance, and not performers. Performance may be based on factors besides the talent and motivation of the individual in question, such as job or market conditions. A person may perform well in some aspects of the job but not in others. Avoid creating a system that plays favorites or denies people the opportunity to improve.

Tie rewards clearly to performance. Ideally, this should be done at both the individual and group (organization and/or team) level. This requires deciding what performance metrics are truly important and being consistent in their application. There is no point to encourage senior employees to mentor juniors, for example, but only reward them for time spent with clients.

These practices are possible regardless of the amount of resources available, with the possible exception of the first.

Managers work within this system and their team members understand that they are constrained by it. Managers who succeed at meeting their team members’ drive to acquire:

- Set clear expectations by which performance is evaluated

- Demand high performance

- Ensure their team members receive rewards and recognition.

Be exceedingly clear on metrics and priorities. People are stretched to the limit: Don’t demand busywork or needless perfectionism.

During this pandemic managers may be the only witnesses of extraordinary efforts employees are making to stay focused and productive. Sincere, informed acknowledgement of these efforts can go a long way. Recognize outstanding accomplishments during meetings or some other way.

For example, gifts and services are appreciated by people more than ever before. Gifts of consumable items are actually valued these days! A fruit basket looks pretty exciting. Especially good are rewards that will ease workers’ daily strains—deliveries, dog-walking, online entertainment or classes for children. With so many companies in flux, it may be possible to get good discounts or in-kind exchanges of items that team members would appreciate. Gift certificates for takeout to local restaurants, personalized miniature embroideries, and online classes in yoga (for adults) and improv (for kids) are only some of the creative rewards managers have given their teams.

Celebrate not only splashy wins but the steadfast, regular business-as-usual activities that are now being accomplished under extraordinary circumstances. Everyone on your team can now add the line “ … during a global pandemic” to their list of job duties. Acknowledge that! At the same time, be authentic and don’t condescend.

Don’t be afraid to give course corrections when necessary. In the words of CEO coach Sabina Nawaz, “Small and frequent performance guidance circumvents major corrections down the road and allows everyone to stay in sync despite distance and daily change.”

Bond/Belong

On the organizational level, this drive is usually satisfied through company culture. Best practices include:

Foster mutual reliance and friendship among coworkers. Much has been written about how to manage remote teams and encourage collegiality. Teams that have only recently gone remote because of the pandemic have a few differences. On the upside, they have already built relationships and can leverage those. On the downside, the distance from colleagues and work friends is experienced as a possibly demotivating loss.

Value collaboration and teamwork. There is also the issue that over the next 18 to 24 months some people will return to the office while others continue working from home; this can lead to rival subcultures. Onboarding and integrating new employees is also especially difficult. The major issue with remote workers and motivation appears to be feeling isolated and second-class relative to the onsite workers.

Encourage sharing of best practices. Encourage employees to tell you what they are doing well and how they are lifehacking. Share best practices and praise them.

Managers who meet their teams’ bonding needs:

- Make employees feel a part of the team

- Are people-oriented

- Care about employees on a personal level.

Start meetings with a check-in or opening ritual before diving into business.

Think about creative bonding experiences—an online talent show? Recipe contest? Game night? Show-and-tell of each team member’s favorite piece of art or travel souvenir? These might even be ways for team members to show new skills or facets of their personality.

Zoom fatigue is real. Not all bonding has to be in the moment. Take advantage of asynchronous communication with a page or Slack channel for sharing recipes, articles, and snapshots.

The leveling effect of remote work may make this a good time for cross-team collaboration, assignment rotations, or peer mentorship opportunities. The fact that sales was on the third floor and R&D on the second isn’t quite as relevant as it once was.

Comprehend/Challenge

On the organizational level, this drive is usually satisfied through job design. Best practices include designing jobs that comprise distinct and important roles, have meaning, and foster a sense of contribution to the organization.

This does not mean all jobs must be knowledge work, or that employees must work at the peak of their intellectual or creative capacity to be fulfilled in this drive. There are two main ways that the drive to comprehend is satisfied on the job. The first is through whatever opportunities for learning, problem-solving, and creativity exist in the job itself. The second is through understanding the role and value of the job within the organization. This understanding can transform even mundane jobs.

The many unknowns of the pandemic mean that people’s overall need for comprehension and control is severely stymied. Organizations that can satisfy this drive for their employees will find them highly motivated in return. People are desperate for a chance to feel in control, as if they are making a difference.

Managers meet the drive to comprehend by:

- Empowering team members

- Giving team members challenging assignments

- Helping team members learn and grow.

Do “office hours” on videoconferencing to replace the informal conversations you once had in the office. This will encourage people to come forth with questions, and with observations and suggestions that might not seem important enough for a full meeting.

Job design may have to take a back seat to immediate needs at this moment because some companies may not be able to perform all of their usual functions, and others may be in all-hands-on-deck mode. At the same time, the crisis brings the opportunity to interrogate business practices. Managers should continually connect their employees’ efforts to the organization’s higher-level goals. If they are not able to do this they need to be having conversations with their own bosses. This may be a good time as well to “[Challenge] employees to think more broadly about how they could contribute to making a difference for coworkers, customers, and investors.”

Providing employees with opportunities for continuing education can be highly motivating. At the moment, experts, educators, and entertainers are releasing a great deal of content online due to public events being cancelled. Furloughed or underutilized employees, especially, should be empowered to do continuing education—in things they are interested in, regardless of its apparent relevance to their jobs. Organizations will need creativity in the coming months and years, and the most reliable recipe for it is to collide one way of thinking or body of knowledge up against another. Sign your best salesperson up for those violin-making classes!

Nawaz also recommends:

“Stay ahead of the game by inviting problems, not just solutions. Our previous rules of engagement have gone by the wayside, so no one has definitive solutions. Invite your team to come to you with problems, even if they don’t yet have solutions. Consider saying, ‘In our current world, we all have questions, few people have answers. If you see signs of trouble, issues that aren’t visible to me, don’t wait to come to me until you have an accompanying solution. Bring me your early indicators and together we’ll devise experiments to tackle the challenge.’ Explicitly signaling you want to know about budding problems will enable greater periscopic vision and access to broader sets of solutions.”

Defend/Depend

The drive to defend, though primitive—it’s rooted in the basic fight-or-flight response—is nonetheless complicated. Animals are concerned only with “mine” and “might.” For humans, the defense drive is combined with a sense of justice or fairness. The desire to have something valuable—a well-paying job with a good title, say—is the drive to acquire. The drive to defend is the desire to be known to have deserved the job and gotten it fairly, and to believe that the job will not be capriciously taken away. When this drive is negatively affected, people become fearful, resentful, and disengaged.

On the organizational level, this drive is usually satisfied through performance management and resource allocation systems. Best practices: Processes must be transparent and fair, and their transparency and fairness must be communicated to employees.

Managers who meet the defend drive well:

- Create a psychologically safe environment

- Treat people fairly. Encourage team members to speak up and listen to what they say.

Overcommunicate. Even without economic turmoil remote workers can develop negative attribution tendencies, such as assuming they were left off an email chain because they are being eased out when in fact a simple error might be to blame.

Creating a psychologically safe environment does not mean compromising on performance. Instead, it means acknowledging that mistakes are inevitable, especially in times of learning and transition, and that success consists of surfacing errors and learning from them. Make a clear distinction between mistakes and malfeasance. Allow time for team members to process losses with new technology and altered ways of doing things. Encourage them when necessary. Typing is faster than writing, but not when you’re first learning.

Normalize asking for help. Offer help before it is asked for.

If resources need to be cut, be clear about why. Let employees know that it is acceptable to be frustrated or upset; those emotions are entirely valid. This does not mean condoning unprofessionalism or abuse by any stretch—it means not putting the emotional burden on them to make you feel better about it. Explain the business case, give them time to process.

Integrate the drives, empower the managers

When employees report even a slight enhancement in the fulfillment of any of the four drives, their overall motivation shows a corresponding improvement; however, major advances relative to other companies come from the aggregate effect on all four drives. This effect occurs not just because more drives are being met but because actions taken on several fronts seem to reinforce one another. The holistic approach is worth more than the sum of its constituent parts, even though working on each part adds something.

When these actions come through one person—the manager or team leader—some integration automatically takes place. A course correction serves to hone the competitive edge (acquire), while improving understanding (comprehend), and, if it is delivered in a helpful and respectful way, strengthens the relationship between manager and employee (bond).

Please look to your managers: Do they have what they need to lead and manage? Are they leading, managing, and motivating their employees during these difficult times?

About the authors

Boris Groysberg is the Richard P. Chapman Professor of Business Administration and Robin Abrahams is a research associate at Harvard Business School. This article was originally published on Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.