HBS Faculty Comment on Crisis in Japan

|

BOSTON—As Japan continues to come to grips with the devastating toll exacted by the earthquake within its borders, the aftershocks are just beginning to be felt within the global economy. Here, several Harvard Business School faculty members share their views and insights about the challenges that lie ahead for Japan's business leaders and for global companies operating in Japan.

Rohit Deshpande, Sebastian S. Kresge Professor of Marketing The culture of Japan tends to be outer directed. Thus, taking care of other people becomes much more central to its value system. This is one reason why Japanese companies tend to look out for the welfare of their employees in such an effective fashion. The impact of this at the national level can be seen from the Japanese people's response to previous crises, including the earthquake in Kobe in 1995. The remarkable resilience of the Japanese was clearly in evidence during those times, along with countless acts of heroism by ordinary citizens—people not empowered or trained to do great things. We are seeing this in the horrible aftermath of the current earthquake and tsunami. Consider the reports of my HBS colleague Hiro Takeuchi, a Japanese national who was working in Tokyo last week when tremors hit the city. He left his office to drive home. The usual 10-minute trip lasted four hours. Despite their lack of knowledge of what was happening and the full extent of damages, despite their worst fears based on previous experience, people were relatively calm, he said. He was also impressed by their patience and resilience. There was no pushing and shoving, Takeuchi reported, no honking of car horns, even in long waits for a tank of gas. On the highway, anxious drivers eager to get home to see if their families were safe remained in their lanes. All this makes for a case study of the moral courage of ordinary Japanese citizens in times of crisis. There are lessons to be learned here by the rest of us.

W. Carl Kester, George Fisher Baker Jr. Professor of Business Administration Human suffering is certainly our main concern in the immediate aftermath of Japan's 3/11 tragedy. But even as we focus on immediate human needs, we cannot avoid recognizing –" and coping with –" the long economic shadow cast by this disaster. The direct impact on real economic activity worldwide is already being felt. The destruction will surely cost Japan many times the $132 billion that the 1995 Kobe earthquake did, making it one of the Japan's most costly natural disasters. Transportation disruptions and the closing of many factories throughout Japan will shrink Japanese aggregate demand and disrupt supply chains worldwide. Analysts have already reduced forecasted GDP growth rates for Japan by 0.5% for the first quarter of this year, and by more than 1.5% for the second quarter. The financial consequences are equally alarming. The Nikkei 225 Stock Average plunged 6.2% at the market's close on Monday (3/14), erasing more than $300 billion of equity value, and lost another 10.6% on Tuesday. These are no mere "paper" losses. The drop represents a significant loss of wealth which could unleash further deflationary pressures –" a phenomenon Japan's on-again, off-again economy has been fighting for almost two decades. Japan's economic policy makers are being put to the test once again. Flooding money markets on Sunday (3/13) with Â¥15 trillion (about $183 billion) was a sensible first step by the Bank of Japan, but the real challenge lies ahead. Prime Minister Naoko Kan's government, still young and struggling for public support, is left with the task of fashioning an appropriate fiscal response. Bold recovery plans would seem to be in order, but how that response is financed holds great import for Japan's economic future. With government deficits equaling 10% of GDP, and national debt at 200% of GDP, funding the recovery plan with still more government debt would be imprudent. Should Japan lose its AA- sovereign debt rating, confidence in the country's economy and government could be sent into a debilitating tailspin. A safer, even if less popular, course of action would be to reprioritize spending within the existing budget to cover most of the cost of the recovery plan. Japan often shows itself at its best in times of crisis, setting aside internal differences and responding with inspiring levels of efficiency and self-sacrifice. This crisis will be no different as far as its response to humanitarian needs is concerned. Hopefully, the longer-term economic response will also be executed in ways that will avoid unleashing yet another round of deflationary forces. Unfortunately, there is little margin for error this time.

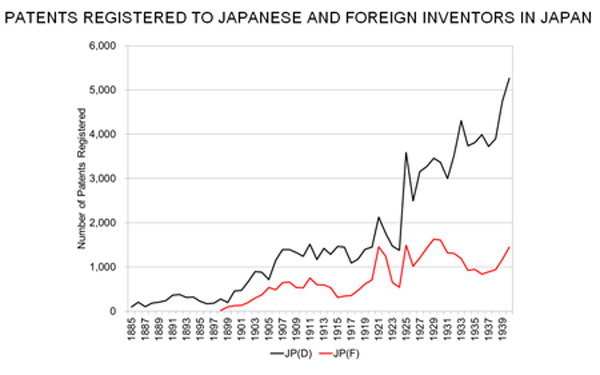

Tom Nicholas, Associate Professor of Business Administration Just before noon in September 1923, the Kanto region (where Tokyo is located) was affected by a strong earthquake. The Grand Kanto Earthquake, as it has become known, led to the destruction of Tokyo and Yokohama. Over 100,000 people lost their lives. Despite the severity of the earthquake and its aftermath, the country quickly recovered in key areas of economic activity. Consider patents as a proxy for resources devoted to innovation. In 1923 and 1924, patents registered in Japan fell by around one-third compared to 1922, the year before the Grand Kanto Earthquake. But by 1925 (even though the Japanese Patent Office in Tokyo was destroyed) patents registered were 69 percent higher than they had been in 1922, and the country continued its push towards technological modernization (see figure below). The Grand Kanto Earthquake only temporarily interrupted patenting activity. A long-run expansion in Japanese technological capabilities set a favorable foundation for the economic growth miracle the country experienced after World War II. If history is any guide, Japan should make a full recovery from the devastating effects of the recent earthquake and tsunami on the east coast of Honshu.

Notes: Japanese domestic JP(D) and foreign inventors JP(F) patenting in Japan. Source: Tom Nicholas, "The Origins of Japanese Technological Modernization", Explorations in Economic History (2011, forthcoming). http://people.hbs.edu/tnicholas/Jmod.pdf

Willy C. Shih, Professor of Management Practice Beyond the devastating and saddening human costs, the earthquake in Japan is another reminder of the complexity of the world's supply chains and the great interdependencies in global production systems. The world's supply chains are complex and highly optimized to deliver products efficiently at the lowest cost. They are characterized by a sequential mode of production where goods are produced in a series of stages in different countries by vertical specialists who pass them across borders to the next firm in the value chain. Shocks like this ripple through the chain, and test the robustness of their design. With lean inventories and just in time deliveries, there is not a lot of slack in the system to act as a buffer. This disaster promises to be quite a test. Consider, for example, Shin-Etsu Handotai, one of the world's leading producers of the silicon wafers and ingots that are used in the manufacture of semiconductors. Its Shirakawa plant is located in Fukushima, close to the epicenter of the earthquake and near the site of the nuclear power plant troubles. That plant is responsible for 22% of the world's supply of silicon wafers, and it has been shut down for lack of electric power. Hopefully this is temporary, but imagine taking 22% of the global supply of a vital commodity offline. Toshiba is a Japanese company that makes 35% of the flash memory in the world, consumed by devices like Apple's iPad and smartphones. It has not disclosed yet how the earthquake has affected its business, but major DRAM memory chip makers like Samsung and Hynix in Korea, and Powerchip in Taiwan have already stopped quoting prices until they can assess the impact of the earthquake on their supply chains. Anisotropic conductive film is a key material used in the manufacture of LCD flat panel displays in TV sets, notebook computers, smartphones, and tablets. 70% of the world supply comes from Japan, and as of March 16th, suppliers have stopped taking orders. Most of the world supply of LCD panels comes from Korea, Taiwan, or China. All of Sony's lithium battery cell plants are in Fukushima in the disaster area, and many of its suppliers are as well. This has the potential to affect the supply of notebook computers, even though almost notebooks are assembled in China. Japanese automakers also have significant component production in the affected area, and even for factories located at a distance from the epicenter, the rotating power outages promise to be a significant near term challenge. An e-mail exchange with a good friend at a major Japanese multinational over the weekend highlighted for me the uncertainty that lies ahead. After spending four hours walking home because the trains weren't running in Tokyo, he told me that some major manufacturers have stopped operations not only because of damages to their own facilities, but because of damages to their parts suppliers and subcontractors located in the region. |

About Harvard Business School

Harvard Business School, located on a 40-acre campus in Boston, was founded in 1908 as part of Harvard University. It is among the world's most trusted sources of management education and thought leadership. For more than a century, the School's faculty has combined a passion for teaching with rigorous research conducted alongside practitioners at world-leading organizations to educate leaders who make a difference in the world. Through a dynamic ecosystem of research, learning, and entrepreneurship that includes MBA, Doctoral, Executive Education, and Online programs, as well as numerous initiatives, centers, institutes, and labs, Harvard Business School fosters bold new ideas and collaborative learning networks that shape the future of business.