Pre-performance rituals are the stuff of legend for musicians and athletes—Keith Richards eats Shepherd’s pie before every Rolling Stones concert (and must be the one to break the crust); Beyoncé prays and stretches with her band members; Tiger Woods wears red on the course. And while leading a case discussion in an MBA classroom might not be the same as singing to thousands in an arena or teeing up at the Masters, it is a practice that often inspires anxiety. We talked with four professors at HBS about how they use rituals in their teaching.

When Mike Norton, the Harold M. Brierley Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, heads to the classroom, he makes sure to always carry the one item that he would feel lost without: the leather binder his father gave him 25 years ago. The binder, which holds his teaching plan written on yellow paper (always), has accompanied him to every class he has ever taught at the School. It’s a tool that helps Norton center himself before he digs into a lively case discussion—a reliable ritual that ensures a successful session. The role of such a device is one he recognizes from years of research on how rituals influence human behavior.

Norton’s interest in this area was sparked by his earlier work examining how different cultures deploy rituals for a wide range of uses, from births to marriages to death, and even to organizational practices designed to promote cohesion. When Alison Wood Brooks, the O'Brien Associate Professor of Business Administration, joined the HBS faculty, she was working on a paper about how performance anxiety can be assuaged by reframing the sentiment as excitement. Could a pre-performance ritual also affect anxiety levels? In their resulting collaboration they asked participants to sing karaoke, and measured the heart rate and performance skill of two separate groups—one of which just got up and sang, and another who drew a picture of their feelings, then crumpled it up and threw it away. Those with the pre-performance ritual were less stressed and performed better—not like a pro, laughed Norton, but better and with more confidence.

“In many domains of ritual there is an element of control,” said Norton. “The orderliness of rituals makes us feel a bit more in control of things—we’re not, the world is not in our control—but there is a sense that if you can do this repeated, familiar set of steps, it increases your sense of control and ability to get done what needs to get done.”

For Eva Ascarza, the Jakurski Family Associate Professor of Business Administration, rituals are all in service of devoting her mind solely to the case discussion. First and foremost is printing out her “logistics” document: a list of her pre-class tasks, items to take to the classroom, things to memorize or practice pronouncing, and the students she’s planning to cold-call that day. She also brings her plan for the blackboard and a Post-it note with the end-time of class. Once class begins, she never glances at any of those things—but it’s essential that they’re there.

“I do all of these things in anticipation of not wanting to think about anything that is not class related,” says Ascarza. “I don’t have a great memory, so all I want is to not have to remember the name of my cold calls or that I have to bring water and my glasses. This is to have peace of mind so that I can rely on my brain to focus on the class.”

The case method requires this type of dedication, she says—she never needed them in her previous teaching roles and doesn’t when she gives research talks. “Before HBS I taught lecture classes and only cared about the content I was going to deliver. Here, I’m paying a lot of attention to what students are saying—I want to connect points and orchestrate the conversation towards a learning point. That cognitive capacity is more complex—I need to really concentrate my attention, so all of my resources are devoted to that.”

Once she’s in class, she has a few rituals she always adheres to: welcoming students with “Good morning, how are you?” and walking up and down the stairs furthest from the student she has cold-called as she listens to their response.

A quick, short espresso before class is the last thing Ascarza notes as vital—but that, she laughs, is a physiological necessity, more than a ritual.

A self-professed obsessive over-preparer, Jan Rivkin, the C. Roland Christensen Professor of Business Administration, says rituals help him enjoy the inevitable, desirable uncertainty of the case-method classroom. One particular practice that he developed early in his 25-year HBS teaching career, he deems essential: memorizing one thing about each student. A week before a new course starts, Rivkin fills out a spreadsheet with each student’s name and various facts—undergraduate institution, primary work experience, name pronunciation, and any other interesting item of note. Then, he writes each student’s name and a single fact about them on an empty classroom seating chart. He then pulls out another blank seating chart and tries to fill it out without referencing the original. He repeats it again, and again, and again—as many times as necessary to get it all correct. For the week before the first class, he does it every day.

“I feel deeply that I can be more effective if I know a little about my students before class begins. It’s not very time consuming: in about two and a half hours, I can know one thing about each person,” says Rivkin. “It is tremendously beneficial in a number of ways. First, I will notice things that might be relevant to particular cases. Second, for some reason I’m better able to remember what people say if I know something about them. Third, it reminds me of how remarkable our student body is and how blessed I am to teach this group with their full diversity of experiences and backgrounds.”

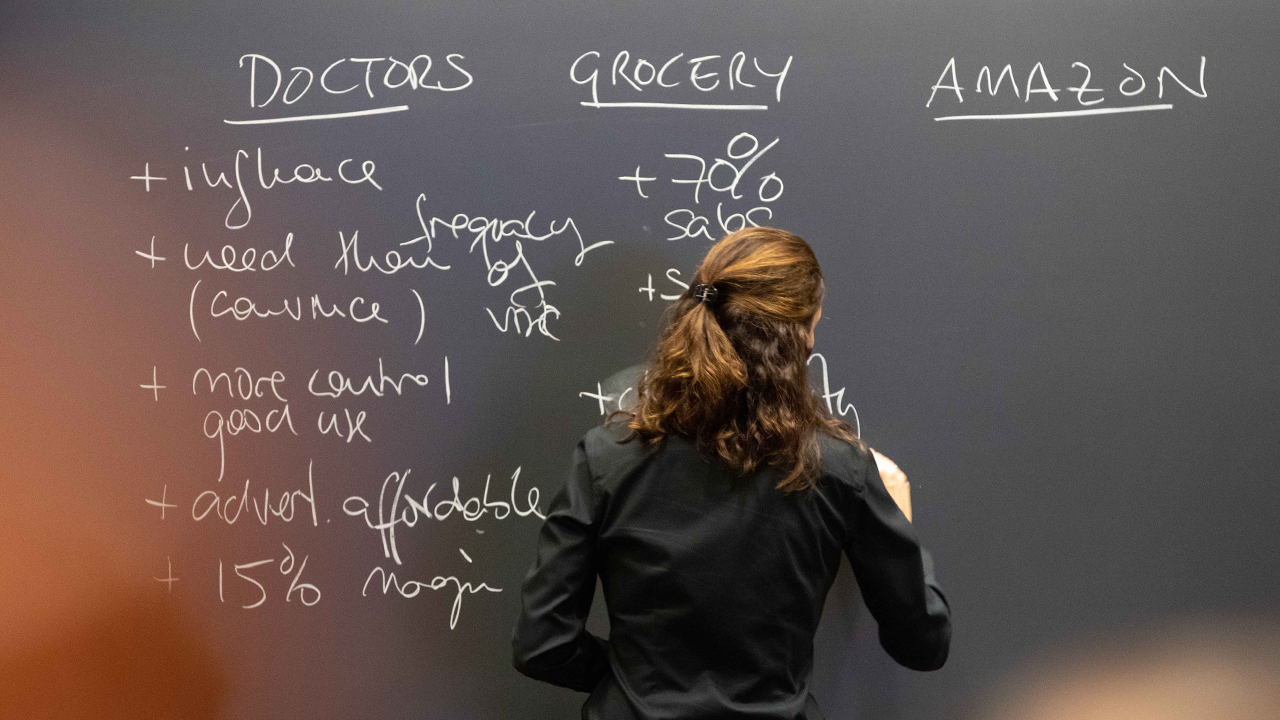

On the walk to class, Rivkin reminds himself of the one critical objective of the class—there may be many points to get across, but there is always one that is crucial to the overall course objective. Once inside the classroom, the rituals continue: the case, teaching notes, slides, seating chart, and board plan are always in precisely the same place atop the instructor’s desk; a drink is on the left side of the desk, the colored chalk on the right; the chalkboards are arranged just-so. “My notes have to be in the right place,” Rivkin laughs, “even though I never look at them during class.”

“I’m one of the more obsessive individuals,” he adds. “I have colleagues who find this much structure to be a burden and an obstacle to a good conversation. They are every bit as prepared as I am, just in a different way. For me, it turns out the more structured my setup is, the more spontaneous I can be with my students.”

Assistant Professor Jaya Wen considers teaching to be an expression of her creative energy, and sees the rituals she undertakes prior to class as tools to marshal that energy on demand. “The deep puzzle of both research and teaching is how you can get into the zone in a creative way and be able to do that at, say, 9:10 am on Tuesday when you have to show up to class,” says Wen.

She’s learned over time that waking early, beating traffic, getting a coffee and a bite to eat at Spangler, and “hermiting” herself in her office for a few hours allows her to arrive in class ready to teach and engage in discussion. “I speed read the entire case, consult my teaching plan, think about every source of interesting tension that I can get into—I basically load everything into working memory,” she says. Fifteen minutes before walking into class she memorizes the names of students whose voices she wants in the conversation. “For me, it’s setting the intention and getting my mind and body working together as one. Ritual is very important. When I invest in those rituals, I tend to have a better workday.”

Wen’s background as a competitive debater has shaped her approach to learning and teaching—leading a case discussion is ultimately trying to create a debate rooted in the facts and integrating multiple perspectives.

“Part of why case teaching is so challenging is because you really have to master the substance and all of the logistics beforehand. Once you’re in the classroom it’s all instinct, and the way you can hone your instinct to be good enough is to be really, really prepared. So that’s my strategy.”

This article was originally published by the HBS Newsroom.